Set in the Sarpi–Canonica district, the history of Milan’s Chinatown mirrors the struggles and success of a community that’s claimed a larger role in Italy’s fashion capital

Milan Cortina posters with the Winter Olympic mascots, Tina and Milo line the streets of via Dante, as I make my past glitzy shops and the aroma of Italian food being served to customers. Up ahead, the imposing Medieval Castello Sforzesco appears, indicating I’m within two kilometers of another historical, trendy area in the northwest section of Italy’s fashion capital: Milan’s Chinatown.

The street sign Via Bramante appears and Mandarin chatter can be heard around every corner. Chinese men playing chui niu (吹牛) at bars, overtakes place the mingling of Italian’s over aperitivos. Store signage begin to display Chinese characters and Chinese food is around every corner. I’ve arrived in the heart of Chinatown, known in Italian as Quartiere Cinese, the “Chinese Quarter.”

Yet, today’s bumping, modernizing neighborhood is a vastly different scene from its pre-world war II origins, and eighteen years ago when a small fine flipped the pages on the region’s future identity and cultural roots.

Chinatown History in Milan

Along Via Paolo Sarpi, the district’s main commercial strip, the predominance of business owners from southern Zhejiang—especially Wenzhou and Qingtian—is readily apparent. “There are migrants from Fujian and from Northeast China too, but the predominant cultural and social character was shaped by Wenzhounese migrants,” says Zhang Gaoheng, an associate professor at the University of British Columbia.

Among the first Wenzhounese to emigrate over were skilled in agricultural-related fields and veteran stonemasons, experts in carving pale-green soapstone. The 1990s saw a major migration of Chinese moving from northern to southern Europe, driven by new employment opportunities or to reconnect with family members with established businesses in Spain, Italy, and France. During the same period, 95% of the 165,000 Wenzhou migrants in Europe were estimated to live in France, the Netherlands, Italy, and Spain.

“Milan housed what was the first real Chinese community in Italy, numbering 175 in 1936, becoming larger during the 1950s and 1960s,” says Patrizia Battialani, a Chinese migration researcher and economic history professor at the University of Bologna. “The small number and common origin of most Chinese migrants of the 30s and 50s, almost all from Qingtian.”

Situated near Milan’s historical center, Borgo delgi Orolani (the neighborhood of greengrocers), was once a low-income neighborhood. Gradually it developed into an industrial district that attracted craftsmen of various trades. The beginning of the 18th century saw multistory units sprouting up, expanding westward to the nearby Canonica Sarpi neighborhood. The relatively cheaper neighborhood began attracting Italian residents of various income classes and immigrants of various backgrounds. Mixed marriages between Chinese and Italian resulted in an increasingly dense and more commercialized neighborhood. By the 1940s, Chinese immigrants formed the most prominent minority group, and Canonica Sarpi gained a new moniker, “quartiere generale dei cinesi” — headquarters of the Chinese.

Chinatown’s Transitioning Economy

Today’s thriving, retail-focused scene may have looked entirely different if it hadn’t emerged from a series of challenges in previous years. Following along with the wave on new Chinese immigrants in the 1990s, manufacturing and wholesaling businesses began to rapidly emerge.

Slowly, the local cultural fabric began to experience a shift. Via Paolo Sarpi’s kilometer-long, narrow cobblestone street was often congested with wholesale supply trucks unloading new merchandise, eventually developing into one of a few, increasingly contentious issues. Tensions between the two communities began to rise, as local Italians, irate with the area’s fast-paced lifestyle changes, ongoing traffic jams, expansion of Chinese wholesale businesses, and rapidly changing community culture had reached a breaking point.

Tensions reached a tipping point in April 2017, when a Chinese woman was given a €40 parking ticket by Italian traffic officials, for unloading new shoes from a car. Sensing injustice and targeting of the Chinese community, over 300 Chinese clashed with Italian police, resulting in a riot. Then Milan Mayor Letizia Moratti remarked, “We will not tolerate having no-go areas in the city. It is outrageous that such incidents should be sparked by a violation of road regulations.” After the riot, the once truck-filled Via Paolo Sarpi, pedestrianized, transitioning into a retail-focused district. Many of the wholesale business owners relocated to the outer districts of Milan.

“Since the end of the 20th century, the Italian economy has shifted from manufacturing to the service sector. Some Chinese entrepreneurs continue to operate in the traditional clothing and textile sector, contributing to the ‘Made in Italy’ production chain in Italy,” says Prof. Battialani. “Others have moved towards the tertiary sector, becoming bartenders, hairdressers, real estate agents, wholesalers, retailers, and consultants.” Though a majority of wholesale businesses have left, Chinese businesses still maintain a heavy presence. “In Milan at least, there was a major debate about spatial politics in terms of how many Chinese businesses vs Italian ones, especially during the 2000s and 2010s. Now things seem more settled and basically Chinese businesses have occupied a majority of commercial spaces available on Via Sarpi,” says Zhang.

Rise of a New Chinese Business Community

Nearly a third of Chinese immigrants in Italy have settled in Milan and Prato — the latter a small Tuscan town of under 200,000 residents, now home to nearly 50,000 Chinese. “During the 1980s and 1990s in particular, the Italian economy was strong and various industrial sectors—including what later on became a dominant Chinese migrant sector, the fast fashion sector—needed cheap labor. The garment industry is also an “easy” sector for unskilled laborers to tap into. The large numbers of Chinese migrants in Milan (and in Prato) began changing the face of the city,” says Zhang.

Located 300 kilometers southwest of Milan, Prato, once known for its traditional textile manufacturing, has transformed into a hub for Chinese-owned garment factories, igniting a discussion around the authenticity of the “Made in Italy” label. Often touted as the height of Italian craftsmanship, various Milanese luxury brands are becoming increasingly scrutinized for their business practices of sourcing from Prato’s Chinese-run apparel factories and sweatshops.

Battialani states that Chinese immigrants have been adjusting with the economic trends in Italy. “In the 1950s, Chinese businesses shared the Italian economic miracle with the local population and lived the “Italian dream,” based on home and car ownership, and the enjoyment of modern conveniences such as television and other lifestyle factors such as going on holiday.”

Changing consumer habits and increases in labor costs, have forced Chinese businesses and entrepreneurs to adapt. “Since the end of the twentieth century, the Italian economy has shifted towards the service sector and many manufacturing companies have closed or moved to countries with lower labor costs.”

Up ahead, a line of customers is forming at Mr. Bao (包鲜生), a small family-owned dumpling stall. A young Chinese lad is busy swapping out bamboo steaming trays, pouring dumplings into boiling water, and blurting out Italian to customers, while his mother hastily puts together the orders. “I’ve been here almost two years. I like it. My mom came over here first, and then I decided to leave Hangzhou too,” Xiao Zhou says as he hands me my order of six soup dumplings.

Reconnection with Chinese Roots

Today, young Chinese, many who have grown up in Italy and graduated from Italian universities are still chasing the entrepreneurial path, using their professional networks to establish high-value, service-oriented and innovative businesses. With the growth of international trade and stronger connections to China, young Chinese entrepreneurs are creating ways to interweave both cultures.

“The situation has changed over time. Currently, the younger generation of Chinese Italians seems to maintain stronger ties with their families’ country of origin. It is also cheaper and less complex to travel from one country to another. As a result, they somehow manage to balance the two cultures, while during the 1950s and 1960s in many cases the younger generations lost all contact with Chinese cultural heritage,” Battialani tells me over email.

“In my own interactions with younger Chinese Italians, or Chinese who grow up and reside in Italy, I find it’s hard to generalize. There are some who barely speak Mandarin Chinese and organize their days around people who speak Italian and the Wenzhou dialect. There are many restaurateurs and entrepreneurs,” says Zhang.

The restaurant scene has become a noticeable example. Italian born Chinese-Italian entrepreneur Marco Liu founded Ba Restaraunt in 2011, introducing a more contemporary-style of Chinese cuisine. Serica, a Milan-based creative Italian-Chinese fusion restaurant founded by Mauro Yap and chef Chang Liu, look to introduce Milan to a new restaurant concept.

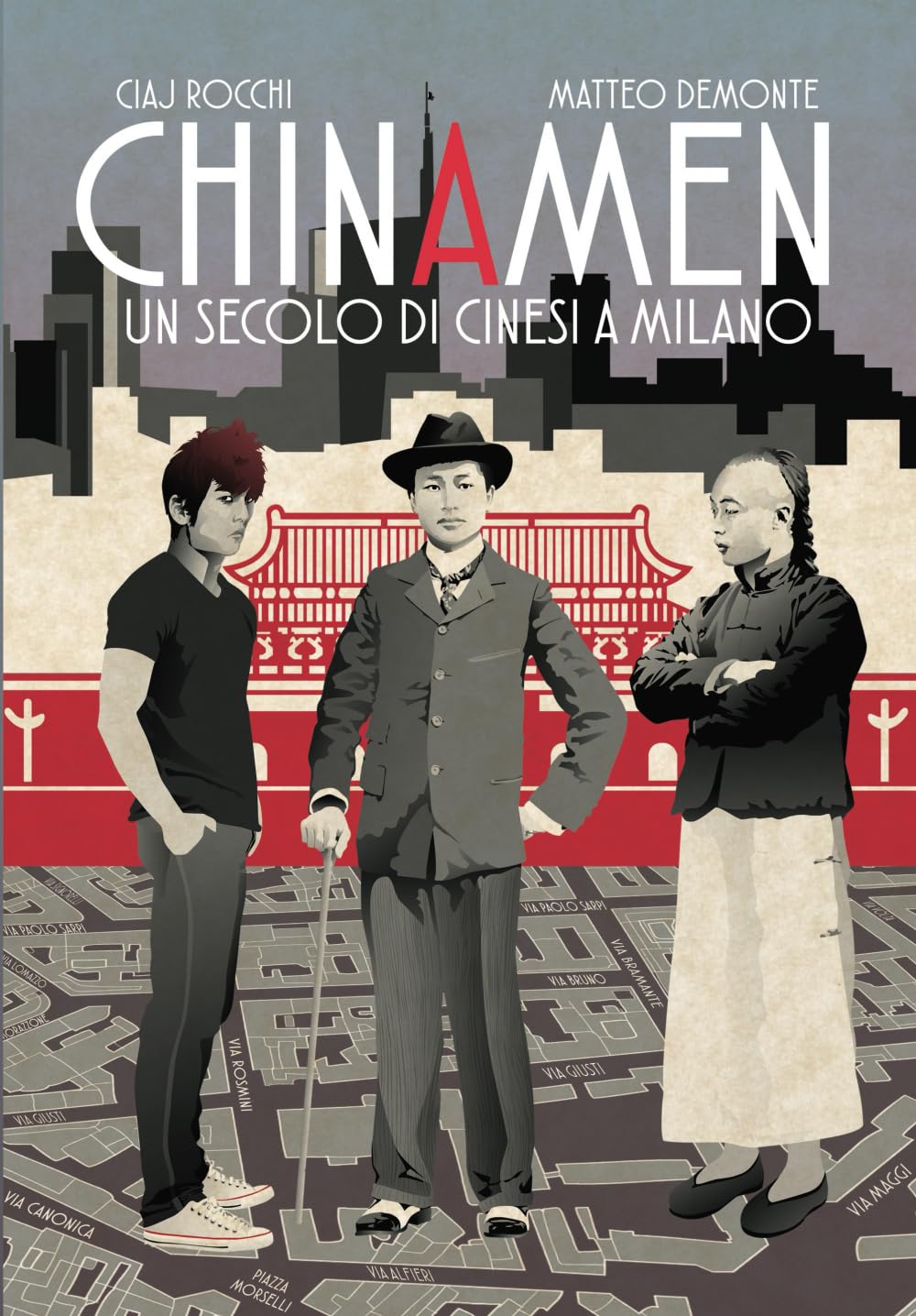

Younger generations of Italian-Chinese, such as Matteo Demonte, are retracing family history to reshare Chinatown history in Milan. “Five years he discovered that his grandfather was one of the first Chinese to arrive in Italy. With his wife, they created a graphic novel regarding the history of Chinatown community. It’s called Chinaman. Next year, they will have a new publication, which will be a collection of eight stories, which connects eight immortal Taoist gods with the eight stories of eight different Italian and Chinese,” says Manganotti.

Changing Chinatown, Changing Milan

Chinese culture is finding ways to weave its identity with local Italian society, giving hope to the next generation of Italian-born Chinese creatives. In 2024, Via Sarpi was a hotspot during Milan Design Week, showcasing a variety of creative Chinese artists who focused on bridging cultural background and historical elements from the two ancient countries. The Steam Factory (Fabbrica del Vapore), located just outside Chinatown, has frequently produced and hosted multiple Chinese-focused exhibitions.

Associna, is doing its part to maintain a strong cultural-bridge between the two countries, while weaving through current challenges. “Milan is still a bit more conservative, but the Chinese are a good example of good integration. They are silent, do business on their own, and solve it inside the community. But its a complex situation. Unfortunately, the government is not willing to give a positive view about the Chinese and the Chinese community, but our association (Associna) is trying to create events and opportunities to let people see the good part of the Chinese community,” says Maganotti.

“In Milan at least, there was a major debate about spatial politics in terms of how many Chinese businesses VS Italian ones, especially during the 2000s and 2010s. Now things seem more settled and basically Chinese businesses have occupied a majority of commercial spaces available on Via Sarpi,” says Zhang. Though Milan’s Chinatown may have shed traits of its historical origins, there is still belief that these cultural elements shouldn’t lose their place. “Some places in the Paolo Sarpi district should be dedicated to the valorization of this tangible and intangible heritage,” states Battialani.

It finally begins to cool down as I sit down with a Chinese owner from Wenzhou who runs a small craft beer bar on Via Paolo Sarpi. The owner, who has lived in Milan for over 20 years, pours me a fresh glass of craft beer he recommends from brewery Birra La Bergamasca, 60 kilometers east of the city. “Italians love their lagers,” he says with a chuckle. Three years since opening the bar, he says he’s happy living the Italian lifestyle. “Everything is slower-paced. My kids grew up here and go to college here now too. We’re used to it.” Nevertheless, he keeps a sharp eye on his outdoor seating area, scanning for freeloaders. “I have to pay the city a tax just to have this outdoor seating. Customers have to pay first.”

I begin heading back to my hotel to prepare for my trip to southern Italy and Matera. I slowly take one last stroll on Via Paolo Sarpi, amid the noise and neon, taking in the history and tradition of a district still defining its place in Milan’s story. Milan’s Sarpi district is undergoing a challenging transition period, but with its history of finding solutions, adaptability to sensitive situations, and evolvement that caters to multiple communities, it may have become the beacon for other Chinatowns to follow.