Journey through Matera’s Sassi districts—symbols of resilience in an ancient city that teetered on the brink of abandonment

Home to ancient Rupestrian churches and cave dwellings carved into limestone cliffs on the edge of a ravine, the Sassi districts of Matera have recently emerged as one of southern Italy’s cultural wonders. Often cited as one of the world’s oldest living cities in terms of continual human habitation, records show human existence in Matera dating back to the Paleolithic era (10,000 B.C.). Yet despite its deep history, the culturally intact Matera has also overcome centuries of hardships and challenges, on its path to establishing itself as an up-and-coming destination in southern Italy.

Representing a distinct lifestyle, the stone caves of Matera have become a source of intrigue for both scholars and tourists in recent years. For Matera, a hidden gem in Italy’s less-often visited Basilicata region, the city has slowly carved a path forward in redefining itself. From being selected as the 2019 European Capital of Culture, to its scenic backgrounds in major films such as the James Bond film No Time to Die, Matera has positioned itself as a new getaway destination in the often overlooked Basilicata region.

After taking an early four hour Flixbus ride from the gritty, vibrant seaside city of Naples, I finally got off at the bus stop on Via Don Luigi Sturzo. With the birds still chirping and the sky, still a mixture of pink hues, I hailed the closest taxi over to the Palombaro lungo, to grab an espresso and begin my journey through Matera.

Underground Descent and the Belvedere Luigi Guerricchio

Today, Matera is a quiet city of nearly 60,000 people that has gradually developed into a new, tourist attraction focused around the Sassi, or “district of stone dwellings” in Italian. Most of the city’s sought out cave-related travel points are situated on the city’s eastern side, with the Sassi region broken up into the Sassi Caveoso and Sassi Barisano districts. Hovering over the Gravine di Matera, over 15,000 cave dwellings can be seen carved into the limestone alongside the rocky canyon.

I decided to start my morning by visiting one of the city’s latest discoveries, the Palombaro lungo, the largest manmade cistern in Matera. After being discovered in 1991, the Palombaro lungo, one of five cisterns in the ancient city and capable of holding nearly 5 million liters of water, led local officials to further explore the city’s complete subterranean cisterns. Ten euro’s allows one to venture beneath to explore one of the city’s more mysterious regions, as well as an opportunity to gain a deeper understandings of the town’s expertise and connection with caves.

Dating back to the 16th century and sitting 200 feet below Piazza Vittorio Veneto, the underground cavern has played various roles over the years. Acting as a cold storage facility for ice blocks, a space for tanneries, a cellar for wine, and public water source for the city’s wells, the cisterns were key in allowing Matera to sustain continuous habitation for so many years. Walking along the sturdy, wooden boardwalks, the mouths of the wells above peak out throughout. Dim lighting and the sound of dripping water echo in the distance as tourists soak in the cistern’s staggering size. After a quick twenty-minute stroll, I decided to head back up towards the sunlight and to catch one of the city’s most scenic viewing points.

Directly across is one of the most scenic viewing points for shots of Matera’s Sassi districts — the Belvedere Luigi Guerricchio, or ‘Tre Archi.’ The stunning backdrop allows visitors to witness the beauty of the Sassi and its incredible hilly, stony layout. Stone buildings stacked atop each other, as winding alleys lighting up beautifully at night, disappearing behind the maze of tiled roofs. Green hints of trees and cactus plants on balconies add a splash of contrasting colors against the creamy stone walls. Tourists scurry around various corners hunting for the perfect cave angle. Humming along with beats of old Italian men playing accordions playing in the background, I begin walking down from the terrace and towards the Sassi Barisano.

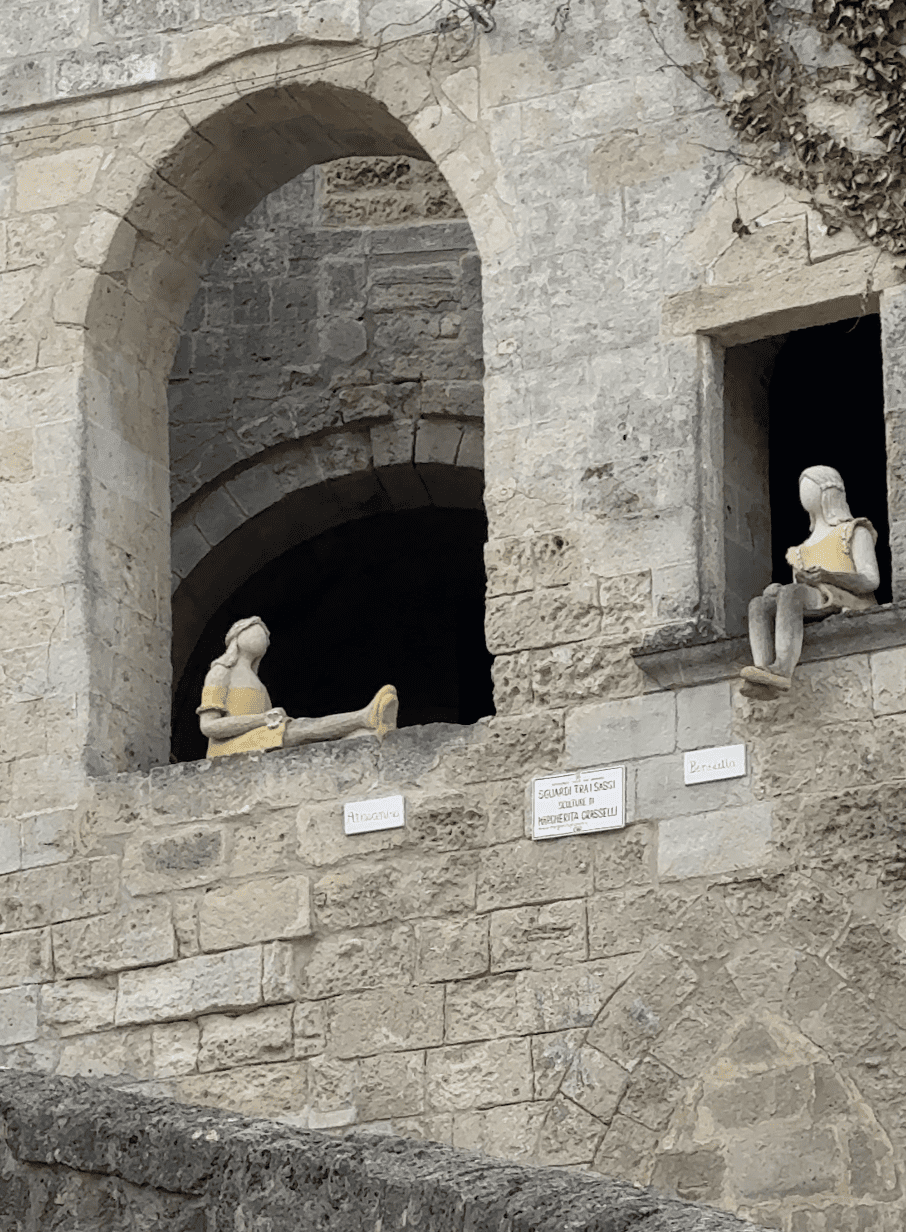

Miniature female figurines, wearing yellow dresses, perched atop windowsills are some of the more unexpected, but distinctive sights along Via Fiorentini. While the city’s beauty and romantic sunset are stunning, it can’t be appreciated without understanding how the city nearly escaped becoming an abandoned place.

Wool-fueled Economy

Among the world’s oldest continuously living settlements, Matera underwent various challenging periods. One of Europe’s oldest cities, Matera steadily developed and reached a golden period during the Late Middle Ages. Wool had become a pivotal part of the Italian economy from the 13th through 16th centuries, when Florence was flourishing as one of Europe’s greatest wool-manufacturing capitals. Matera, with it’s suitable grazing lands, developed into a hub for both wool production and processing. The local economy became highly dependent on the wool trade as a trading stop for wool traders, who ventured south all the way to Puglia.

Yet, by the late 18th century, Matera had entered a period of decline. The Industrial Revolution had reshaped the wool trade, shifting control to England, with mechanized production meeting a new surge in demand. As wool processing expanded, much of the industry moved to Australia, sidelining southern Italy and accelerating poverty across the region. In 1806, Basilicata’s moved its capital from Matera to Potenza, further stripping Matera of resources and strategic importance.

The Shame of Italy

In 1861, Italy was reunified and the Catholic church reclaimed all agricultural lands, forcing local farmers to move within Matera’s Sassi district. With a sudden increase in population, and insufficient open living space, residents were forced to pack into the tight, often one-room cave dwellings. The Sassi were not originally designed to be used as living quarters, but as storage spaces. Gradually, overcrowding became a major issue, with the Sassi cave dwellings often used as mixed living quarters. Old photos show livestock living directly behind family beds. Maintenance of the previously well-managed water networks and drainage systems slowly began to falter.

Various diseases, including malaria had already ravaged the city of caves for the past few centuries. Yet, the already deplorable living conditions, became even more dire, as conditions worsened. Eventually, the Sassi became a hub for various other diseases to thrive within, including tuberculosis and trachoma. Infant mortality rates reached nearly fifty percent up until the 1950’s.

It wasn’t until Carlo Levi, an author from Italy’s northwestern Piedimonte region and exiled to southern Italy for his anti-fascist views, that Matera was brought into the spotlight. Carlo’s book Christ Stopped at Eboli, released in 1945, immediately brought awareness to Matera’s horrid situation. By the 1950’s, Matera, which at that point had become known as the nations’s disgrace, gained the infamous name the “shame of Italy.” With increased exposure on Matera’s dismal situation, the Italian government became directly involved in 1952. Then Italian Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi’s government passed a special law requiring over 15,000 residents to evacuate to newer housing developments, while Matera’s Sassi and Civita districts were redeveloped.

In the 1980’s, a new law called the La Scaletta lobbied for increased funding and preservation of the historic city of Matera. Residents began to slowly trickle back. New proposals were put forth to transform the Sassi districts into cultural centers, cave dwellings were remodeled into local businesses, and plans were streamlined to make Matera an important heritage site. In 1993, Matera shed off its label as the “shame of Italy” and became a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Symbols of Matera

Strolling through Matera is like finding your way through a stone labyrinth, with walkways around every bend and a set of stairs appearing behind each stone dwelling. Boutique hotels, charming restaurants with stunning views line the stone paths, while iconic Fiat 500’s whisk tourists throughout the cliffside city. After exploring various churches and tasting delicious local delicacies, I found my way walking north along Via San Francesco Paolo Vecchio. A wooden sign with Casa Grotta engraved and cabinets of small trinkets displayed at the front entrance catches my eye.

Walking in the sounds of orcarinas being tested by tourists echoes throughout the small space. One of the Italian artisans, noticing me examining one of the colorful handmade rooster ocarina’s on the shelf, begins to introduce to me to the story behind one of Matera’s symbols.

“The rooster is the lucky charm of the people in Matera. It fights off the bad spirits,” he says. He raises a rooster ocarina teaching me how to get the distinct echoing sound. Delicately positioning his fingers over the two openings, he begins to softly blow into the terracotta wind instrument.

Walking out I take a moment to look out at at the Sassi de Matera and the cluster of signs indicating the various cultural sites in the vicinity. Nearby, a lump of stiff bread sits atop a small wooden table outside the entrance of a bakery. This is pane di Matera—the Bread of Matera—a symbol of the city with a story deeply rooted in its past.

Made with natural sourdough and durum wheat semolina that’s grown in the Bascilicata region, pane di Matera is distinct for its unique shape, artisanal production, and rich history. Families would add their own stamps on top of the bread when kneading, as a way to distinguish their own loaves before taking it to the town’s communal ovens. Due to the resilience of the wheat used, pane di Matera is known to last for longer periods of time without spoiling. Eventually it became a symbol and pride of resilience of the locals.

Continuing the Journey Through Matera

A sticker-tagged street sign lists the various landmarks, churches, and museums in the vicinity. Breathing in the fresh air, I mark out the path towards the ravine across from the city, where biblical frescoes, cave paintings, and sweeping panoramic views await. With the sun at its peak, I leave behind the scent of fresh bread, the water cisterns that once sustained Matera, and stone paths that funnel visitors towards different different chapters of the city’s history.

Hoping to catch the first twinkle of lanterns as dusk settles over Matera, I descend toward a hiking trail that leads deeper into the landscape of cave dwellings—continuing my exploration of a city carved from stone and time.